Name: Megan Farrell-Zweigle

Burning since: Fall 2017

Location: Rochester, NY

When and how did you first pick up a wood burning tool?

Leading up to my wedding in 2017, I was really into hand lettering. I had done a bunch of the decorations for my own, and a ton of signage for other friends ceremonies and random gifts. After I got married (wohoo!), my husband and I both found ourselves in a very odd (but very good) 3 week period where neither of us were working, and we could just spend time settling into our home. I started to feel kind of stagnant in the lettering world, and wanted to switch it up. So I found my dad’s soldering iron, and decided to see if I could burn letters into some (very smelly) driftwood. All it took was that first burn for me to be like, “uh yeah, this could be really cool.”

How did you get your business name, Unstrung Studios?

Well, before lettering, I was making recycled guitar string jewelry under a different business name (lol, like, pick a lane, Meg). I had rebranded, and wanted something to allow for more flexibility in case i decided to branch out from jewelry, but wanted a nod to where I started. I loved the concept of taking something “Unstrung” and making it have a new purpose. It was only later that I realized that Unstrung Studios also oddly connected with my disability journey. I have something called Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, and the way I describe it to people is that my body is like one of those “stand-up-man” dolls with the joints unstrung. All my joints are loose and floppy, and the string “holding” me together doesn’t really know how to do its job. So, I guess “Unstrung Studios” started as a very literal name for a guitar string jewelry business, but has become more of a metaphor for my condition, and how life can change when disability enters the picture.

Have you always been artistic?

In a way? Yes? Yeah, I’ve definitely always been crafty... I was the kid that would spend hours on a diorama, painting all the details just right and creating little figures and furniture from cardboard and random things (hot glue was a favorite). I didn’t realize that I could actually draw until I was maybe, 15? And then it was all I did.

I was one of the “art kids” in high school, that really came to school for art class and free periods which I would spend in art class. But the nice thing in high school art was, that was really all I HAD to focus on. Even my job was artistic (I worked at a paint your own pottery place). When I got to college, I found myself not having as much time as I wanted to draw the intricate, large pieces I wanted to do, so I shifted away from drawing into forms of creativity that I could do in lectures, or pick up for 5 minutes between classes. So I crocheted: a lot. And tried embroidery, and then lettering towards the end.

How much time do you typically spend on art in a given week?

Oof. This is a hard one. I spend a ton of time dreaming and thinking about art I want to create, but time like hands-on the making of art runs anywhere from like 20 hours (a slow week or sick week) to…. well lets just say that during the holiday season I once logged a 60 hour burn week. I can get a bit obsessive about making new things in the week before an update or event.

How did you find your artistic voice/style/specialty?

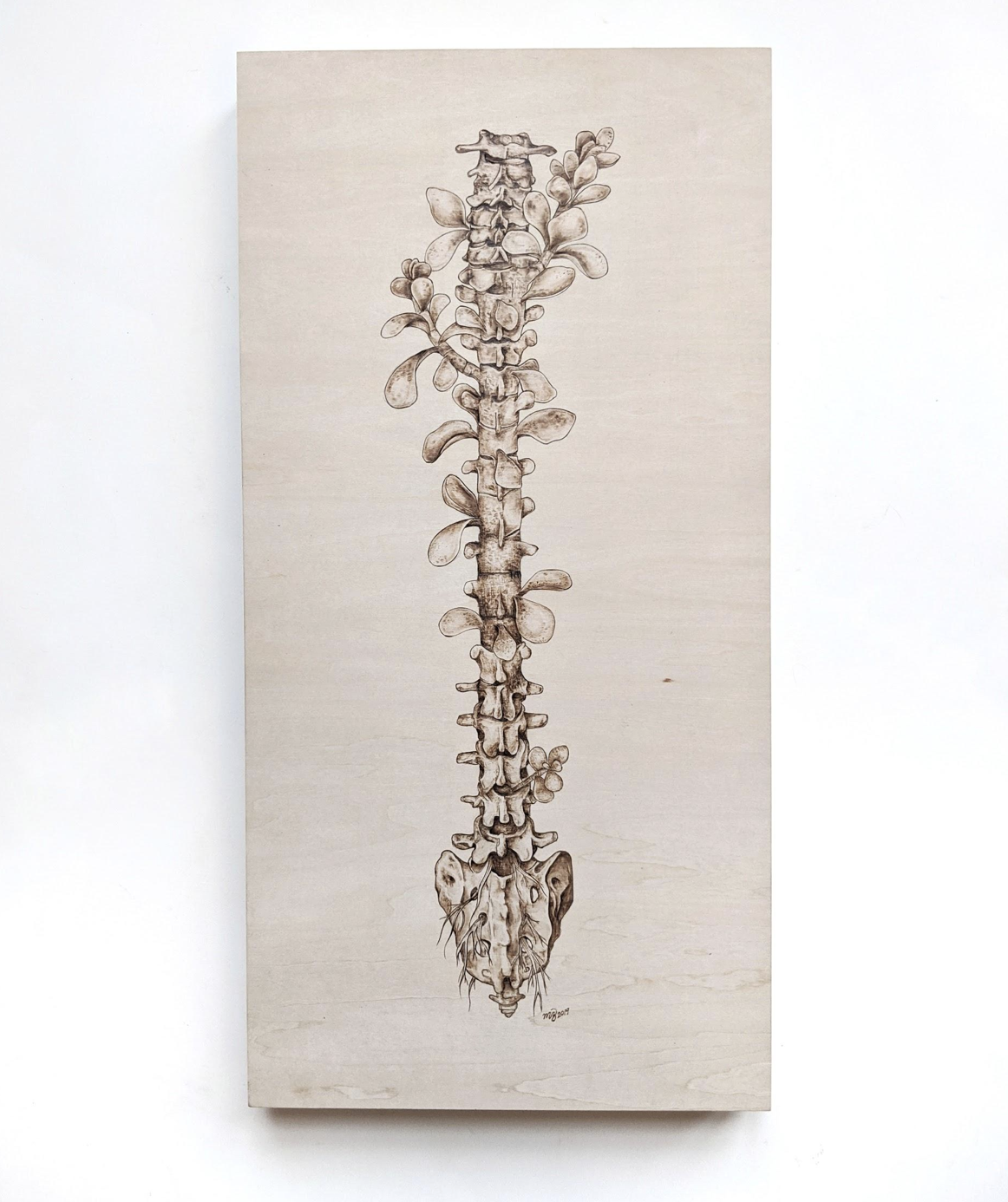

I tried to burn what I thought people wanted, and was miserable (and surprise: people didn’t want it!). I was the happiest when I was making “weird” art, even though a bunch of people told me it wasn’t marketable. So for a while I was trying to do both. Like I would do an anatomy illustration, but then slap a really corny lettered quote on it. Or I’d come up with a weird idea, and sketch it over and over until I had kind of — tamed it down? But then I reached a point where I threw my hands up and was like, “well, if they don’t like it, they don’t like it. I wanna draw weird things” And that’s when I fell into my artistic groove. When I stopped policing my ideas, and stopped sketching watered down versions of my ideas I really started to find my niche, and find out that — as a matter of fact — there are PLENTY of people that love anatomy, love the human body, and want work that can function in both fine art and educational realms.

As far as style? I take a lot of inspiration from classic anatomical illustrations, and have TONS of books just filled with reference photos and drawings. A huge part of my philosophy on artistic inspiration is also this: at least half of your inspiration should come from mediums outside of your own. For that reason, I follow a lot of wood burners,but I follow even more ceramicists, embroidery artists, needle felters, and jewelers. It’s led me to take some the techniques and lines and textures from these various mediums and incorporate them into my woodburning.

How has your disability affected your art in both positive and negative ways?

We’ll go bad news / good news so we can end on a high note.

The hardest part about woodburning physically is that you have to sit upright (for safety). With POTS, there are stretches of days / weeks / months where it can be hard for me to sit upright for more than a half hour at a time without passing out. Because of this, it can be really difficult to get into an artistic flow. I work in a lot of shorter “chunks,” which in some ways is great, but when you’re working on a 3 foot project it can be really discouraging to see progress go so slowly. Sometimes the smoke can trigger migraines, sometimes the migraines mean I can’t see well enough to actually burn anything accurately (or safely), and sometimes my joints are just too painful to hold the pen the way I need to.

On the other hand, my journey with health has been the driving force in my creating art and in me finding my niche. The first anatomical piece I ever did was as a way to cope with my cardiac condition, and to emotionally process a health crisis that my MIL went through. Dealing with my health every day, and trying to keep up with recent research on my conditions means that I am never short on inspiration or new information to incorporate into art pieces.

Teaching about disability, diseases, health and science seem to be part of your mission. Was that always the purpose or did it find you?

I think it was the purpose before I knew it was the purpose! Some of my biggest frustrations are 1) medical misinformation that is shared as fact, and 2) not being able to find the words to explain how I am feeling - physically.

In college I had a friend ask me what it “felt like to be me?” It took like an hour of talking for me to understand that she was really asking was for me to explain how being disabled actually, physically, felt. She was a fellow OT, so I could talk about my symptoms in medical mumbo jumbo and she would understand, but there were other parts of being sick that I just couldn’t figure out how to explain with words. So I started drawing.

Words can be hard, but visuals take the jargon out of the equation. In some ways, I feel like visual representation of physical conditions can be a less intimidating, more direct way to explain to people what something feels like. And even if it is a piece that can be interpreted in different ways, they can be conversation starters. Like my floral stomach: I’ve had people say it resonates with them because of their Chron’s disease, IBD, chronic pain, anorexia, gastroparesis, and more.

The educational aspect for me goes beyond just correct medical information, and includes providing an avenue for people to share their experience with health and disability.

I would love for you to talk a bit about disability advocacy and how we can help.

The biggest thing I’d say is: Normalize access. If you go to a restaurants website and they don’t have anything about their accessibility (where their accessible entrance is, if they even have one, etc), email them and ask for it to be posted. Request for event planners to include access information on their flyers. If you see a wheelchair lift or a curb cut that is blocked by garbage, tables, or advertisements, request for it to be moved, and point out that they’re blocking an entire group of people from accessing their business.

It may seem like a small thing, but when you’re in a wheelchair and you show up to a place that said it was accessible, only to find out that the wheelchair lift is not at all easy to find, it’s outside, and the door to enter is locked from the inside (yep, that happened) it gets old REALLY quick. Making accessibility information public and easily found benefits everyone and hurts literally nobody.

The second (and equally important) part of this is to follow disabled voices, and listen to what we have to say. Did you know that I’d prefer you call me “disabled” rather than “a person with disabilities?” Or did you know that when you tell me that you don’t “see me as disabled,” that actually is NOT a compliment? There’s enough of this topic to make 18 blog posts about it in itself (and people have!), but I’ll leave it at this: when deciding what’s important to disabled people, it’s important to prioritize disabled voices in the conversation.

If you want to know more about any of this, I highly suggest the following accounts to follow on insta/twitter:

OH. Last thing I swear:

caption your videos dang it

Use #CamelHumps for hashtags (that way screen readers identify each word, and don’t just try to read the whole thing as one)

Use Image Descriptions (I need to be better about this!)

What have you learned the hard way that you want to spare other people the pain of learning when it comes to anything wood burning or business related?

Make what you like. Make what you like. Make what you like. I spent almost a year talking myself out of burning anatomy art, for fear that it would be too weird. That year was the most frustrating, unfulfilling artistic year for me.

And clean your dang tips. LOL. I still am awful at this, especially when burning a blackout background. I get so mad because I keep having to turn the heat up, or can’t get a nice smooth black and then I realize it’s because I have so much gunk on my burner! Every time I take 10 minutes to clean my tips I always go back to burning and am like, “Why didn’t I do that sooner!”

What goals do you have for your art or your business?

I have two goal shows: Oddities Flea Market in NYC (Ryan Matthew Cohn if you read this, hi), and doing the OOAK Show in Chicago (also Hi!) but those are big goals, and especially with COVID-19 being what it is, I’m not too keen on putting a timeline on those goals.

My other goals include specific projects that are on my “bucket-list” if you will: burning a kitchen island, kitchen cupboards, a waterfall table, a full skeleton on a table.

Deserted Island with power. You can choose ONE

Burner: Razertip SK (the only burner I’ve ever used, after my dad’s soldering iron)

Nib: Chisel Tip for sure!

Type of wood: Olive Wood!!!

Non-essential tool (but basically essential to you): projector. Or coffee. But probably the projector!

Can you show us some of your favorite tools, must haves? Your favorite nibs? Or hacks?

Oooh yes. So, I have a chisel tip that I have sanded down (sorry Razertip), to be even more narrow for when I am doing teeny line-work on some of my more complex illustrations. Here’s the two tips in comparison:

As far as hacks go, I am a big fan of the projector. With many of my designs, they look best when they fill the wood up a certain way. But if I were to resize and print out a template for every piece of wood, I’d kill so many trees. So instead, I photograph my drawings, digitize them, and then use a projector to get the image onto the wood. That way I can size it PERFECTLY to fit any shape, orientation, or size of wood! It also allows me to see exactly where different knots or colorations in wood will fall within a template. Especially with some of the really intricate designs, it can totally wash out the details if I place them over a darker part of wood, or even over a prominent grain pattern.

You were working on a piece with a brain, can you share that piece with us?

Do you see yourself veering away from anatomy, or are you happy right where you are?

I see myself bringing more INTO anatomy, but don’t see the anatomy going away. I am very happy playing with bones and organs right now, but I enjoying bringing in botany, other animal anatomy, and just generally pushing the limits of what can be incorporated into different structures while still keeping some realism and believability. I have a few pieces with mushrooms coming, some insects, some snakes, but all still have the human body as the main feature.

What’s one piece of advice you would offer to a new pyrographer?

Don’t let other people tell you what to make. And DRAW. I know drawing is hard, and it’s frustrating when things don’t turn out the way you want, but practice practice practice is what will get you there.

Draw what you see, and if it helps? Turn your piece upside down so you are focusing on line and shape, and not having your silly advanced brain focusing on the “whole picture” at one time. It takes you away from “This is what a petal looks like” and lets you focus on the actual, sometimes weird looking, shapes and shades that make things look realistic. I draw and burn upside down all the time!

Watch the recorded live video: